This past Tuesday (22 March 2022), Jeffrey Kripal delivered a lecture “The Superhumanities: Historical Precedents, Moral Objections, New Realities” under the auspices of the University of British Columbia’s Program in the Study of Religion as part, in part, of the kind of promotion that goes on in academic circles for his new book forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press.

Normally, I would have written up my response immediately following the lecture, but I was given pause for two reasons. First, Kripal’s concluding remarks included the confession that he didn’t care if he were wrong. This is no irresponsible shrug of his scholarly shoulders, but, on one hand, an admission of his and all of our human, all-too-human limitations: anyone can be mistaken, even about matters that have concerned them a lifetime; on the other, as he went on to say, any scrutiny of his position and arguments around it push the topic along and keep it, well, topical. I think, too, his words have a more personal sense, one appropriate to a scholar and thinker at a certain stage in their career: he’s invested a life’s work in the matter and, at this point, his sense of the value of what he has accomplished, if only for himself, and what he has set out still to do is unlikely to be very much altered by the kind of criticism it is likely to face in the academic or para-academic milieu. Second, especially in the wake of the Archives of the Impossible conference, which I responded to, as well, I was struck by how, on the one hand (…), certain figures in certain circles can say nothing wrong. Here, I’m thinking of the reception of the plenary sessions delivered by Jacques Vallée, Whitley Strieber, and Diana Pasulka (now Diana Heath, if I understand correctly). On the other hand, these same figures in certain other circles can say nothing right. Such dogmatic stances to the matter at hand fail to do justice to it, if it’s at all as important as Kripal and other invested researchers believe it to be. In this context, my own interventions, when they are understood to be at all critical—and they have been, at times—have been misconstrued as siding with the “skeptics”. So, if Kripal is persuaded of the soundness of his views and any reflections on the matter I might offer will likely be misunderstood (if they’re read by very many at all), I can be forgiven, I think, a certain reflective reticence….

That being said, I am moved to share my thoughts on Kripal’s lecture. In one regard, our respective projects might be said to overlap: his proposed, forthcoming trilogy concerns what he terms “emergent mythologies”, among them that which hovers around the UFO. In another respect, our more fundamental positions might appear to be complementary: Kripal seems intent to disabuse us of a certain received history of modernity, “materialism” or “secularism” (that science and reason have dispelled religion and the belief in and experience of the supernatural or paranormal), while I work around the edges of that technoscientfic hegemony to reveal its historical roots in its Other (religion and magic) and its being embedded and invested in social formations and practices that ground its reification and ideological function, i.e., we’re both critical of a too-comfortable self-image of “advanced society”. Finally, despite his confidence if not comfort in what he believes his scholarship has established to date, as a reader of Nietzsche, he will appreciate that, whatever criticisms I level here, what does not kill his positions might serve to make them stronger.

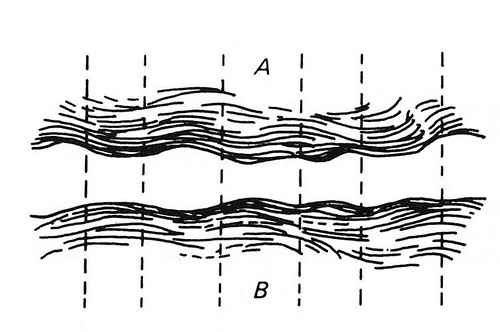

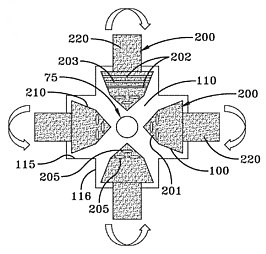

Kripal’s lecture is essentially tripartite. He begins by outlining what back in the days of High Theory would have been termed a “violent hierarchy”, a binary opposition wherein one term is valorized or privileged, in this case, that between science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and the humanities: the former studies objects about which it gathers evidence that it quantifies numerically in order to grasp causal mechanisms underlying the behaviour of nature; the latter studies human subjects by means of the narratives produced by or about them (“anecdotes”); thus the primary data of the humanities is texts whose meaning it seeks to understand. For STEM, physics, nature or matter is absolute; for the humanities, the social. It needs hardly be pointed out that STEM is the valorized term in the context of higher education and society in general. Kripal goes on to posit that psi phenomena trouble if not collapse this opposition, being the space wherein the res extensa of physics and the res cogitans of the mental interact intractably.

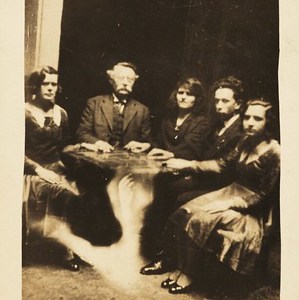

Next, Kripal, as he says, “drops names”: as counter-evidence to Max Weber’s thesis concerning the disenchantment (Entzauberung) of the world in modernity, he reviews prominent figures whose taking seriously psi is generally overlooked or devalued. He refers to Madame Curie’s attending a séance; Immanuel Kant’s interest in the reported clairvoyance of Emmanuel Swedenborg; Schopenhauer’s and Nietzsche’s advocacy of what today we term “paranormal”; William James’ parapsychological research and interest in various hallucinogenics and psychedelics; the writings of W. E. B. Du Bois; Derrida’s putative “conversion to telepathy”; Foucault’s LSD trip in Death Valley and interest in the California counterculture; and the experiences and ideas of recent figures, Gloria Anzaldua and Amitav Ghosh.

To conclude, on the basis of this quick sketch of the repressed or suppressed paranormal, Kripal draws a number of inferences. The humanities have, in a sense, always been shadowed or haunted by the superhumanities, i.e., a grudging, tactful, or marginalized acknowledgement of and serious interest in the paranormal. Such phenomena lend themselves to humanistic study because of their hermeneutic character, i.e., unlike merely natural phenomena that simply “are”, paranormal experiences are often experienced as charged with meaning, the very object of the art of interpretation (hermeneutics). Therefore, this relatively occult history of the humanities’ relation to the paranormal and the character of paranormal experience and of the humanities themselves all suggest that, were this history to be more openly acknowledged and affirmed and the phenomena in question thereby freed from their stigma, the humanities might thereby intellectually and institutionally authorize the paranormal, ontologically, socially, and, most importantly, culturally and spiritually. Or so I understand Kripal’s lecture….

As might be imagined, I have some nits to pick with certain claims Kripal makes and more substantive reservations about his argument in general. No one, I think, familiar with the state of higher education in, at least, North America would find much to disagree with in his estimate of the situation. STEM flourishes while the humanities are starved, with some exceptions, which I will address, below. Kripal’s history of the occulted superhumanities is, however, less persuasive. Most specifically, anyone familiar with Kant, Derrida, and Foucault will be liable to take exception to his readings. Kripal points, first, to the contradiction between the one letter wherein Kant writes of reports of Swedenborg’s powers with no little curious amazement (to Charlotte von Knoblauch, 10 August, 1763 (?)) and the more generally critical work Dreams of a Spirit-Seer Elucidated by Dreams of Metaphysics he published anonymously in 1766 (though he did, in fact, reveal his authorship to friends and colleagues to whom he sent copies of the book) and, second, to the book’s “rhetoric” to argue that Kant was sympathetic to claims made for Swedenborg’s clairvoyance and visions, or so I understand him. The more accepted interpretation of the letter and book is that Kant’s opinion shifted from curiosity to skepticism after having looked further into the matter and having purchased and read Swedenborg’s works, wherein, as Kant writes, “He found what one usually finds when one has no business searching at all, exactly nothing!”. Having come of intellectual age in the Eighties, I’m one of the first to admit one might very well read Kant “against the grain” (“deconstructively”) to thereby show how precisely the rhetoric of the text undermines and contradicts its apparently explicit intent, but that exercise is painstaking and not briefly discharged; one can only wait and see if Kripal undertakes such a demonstration in his forthcoming book. With regards to Derrida’s late text “Telepathy”, I have already noted the challenges of reading it at face value, as taking telepathy literally. Anyone with the time, patience, or hermeneutic fortitude to struggle with and through the text in question itself and survey its reception will see quickly, I wager, it has as much to do with telepathy as Derrida’s more famous Specters of Marx has to do with ghosts in the parapsychological sense. Likewise with Foucault: his readers have long recognized the development of his thinking, from a famous posthumanism that looked forward to the “end of Man” and the disappearance of what in French are called “the human sciences” to his studies on human sexuality and the rediscovery of the human subject in the “art of the self”. Again, one can only wonder if a thorough-going deconstruction of Derrida’s “Telepathy” (which, at the same time, in the name of the rigor characteristic of that “method”, demands a reading, at least, of The Postcard…) is in the offing along with a reading of Foucault’s intellectual development to legitimate offering them as exhibits in his history of the (super)humanities.

The case of Nietzsche is more controversial but no less problematic. Nietzsche plays an important, dual role in the story Kripal would tell. On the one hand, he is an important source of inspiration for all those thinkers too-often all-too-loosely lumped together as “postmodern deconstructionists”—Heidegger, Derrida, & Co—whose influence (or what remains of it) Kripal would like to see displaced. On the other, even moreso than Schopenhauer (with whose work I am not sufficiently well-acquainted to comment on, like that of Du Bois, Anzaldua, or Ghosh), Nietzsche’s affirmation of psi phenomena (e.g., clairvoyance) and his annunciation of the “superman” make him a, if not the, key figure in the story of the suppressed superhumanities. Kripal draws most heavily on the unpublished writings composed around the time of Thus Spake Zarathustra, roughly from 1883 until Nietzsche’s collapse in January, 1889, fortunate enough to be able to refer to the recent English-language translation of the Critical Edition of the Collected Works. I’ll pass over reflecting on Kripal’s preferred translation of the German word for Nietzsche’s problem child, the Übermensch, and the function of that figure in Nietzsche’s thought that would call that translation into question to address the hermeneutic challenge that Kripal seems to, ironically, bypass. With regard to Kant’s text on Swedenborg, Kripal posited in his lecture that its rhetoric undermined its overt dismissal of the seer’s purported powers. However, when it comes to Nietzsche, Kripal seems all-too-ready to take his author’s words at face value, which, to anyone acquainted with Nietzsche’s styles (Derrida calls them “spurs”) and their scholarly reception must seem surprising. As is well-known, Nietzsche was a professor of classical philology and therefore well-acquainted with the rhetorical figures, tropes and schemes catalogued by the classical heritage. He is also recognized as one of the great stylists of the German-language, a style marked by a pronounced indeterminacy. Throughout his work, he employs not only a dizzying shift in tone but dons many masks, personae, among them, famously, “Zarathustra”. However much Nietzsche’s “On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense” might be said to belong to his nay-saying, “deconstructive” period (in Kripal’s telling), the famous passage about truth’s being “a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, [and] anthropomorphisms” holds true for all his writings. It seems therefore a little inconsistent to argue that Kant’s judgements on Swedenborg’s abilities can be called into question if not undermined by the rhetoric of his sobre if somewhat baroque philosophical prose, while pronouncements made by Nietzsche in his (in)famously overtly rhetorical styles can be unproblematically taken at face value.

There is a curious irony in Kripal’s argument about the suppression of the paranormal in the humanities: the more examples he adduces the weaker his argument becomes, i.e., if he shows a consistent concern for what we term the paranormal, then in what sense is there a need for his superhumanities? The matter is far from simple. In outlining his history, he gathers evidence that the humanities, at least since the Eighteenth century, have always been in however repressed a sense the superhumanities. As we’ve seen, he maps a fascination for and engagement with the paranormal from Kant to the present (a not unfateful sample). Listening to him, I was moved to wonder just how ambivalent the humanities’ relation to what we term the paranormal has been. In his history, Kripal remarks William James and his interest in parapsychology, hallucinogens and psychedelics, as if these interests are either unknown or smirked at. However, James’s Varieties of Religious Experience, which touches on Altered States of Consciousness (ASC) in general and their chemical variations, is canonical. In the field of modern philosophy, the place of more esoteric or “mystical” doctrines is well-known and accepted: the Kabbalism of Isaac Luria enters the mainstream of European philosophy first in the work of Spinoza, then by Spinoza’s influence on Jacobi, Hegel, and others. The Neo-Platonism of Renaissance Italy (e.g., that of Ficino) and England also plays a role in that foment of philosophical reflection between Kant and Hegel. Hegel himself, famously, draws out the truth of even phrenology in his Phenomenology of Spirit, and his friend and rival Schelling published a philosophical novel on the death of his wife, Clara or, On Nature’s Connection to the Spirit World. Their contemporary, the playwright and prose writer Heinrich von Kleist, writes a ghost story “The Beggarwoman of Locarno” that presents the matter in an indeterminate manner, leaving the reader having to decide for themselves as to the “reality” of the haunting. English-language literature from the same period to the present displays a similar engagement with “the paranormal”. William Blake was a visionary, who looked “not with but through the eye” for models for his drawings and paintings. Walt Whitman’s sudden inspiration that bloomed as Leaves of Grass is attributed to his undergoing a mystical experience of “cosmic consciousness“. William Butler Yeats’ interest in ghosts, “the Fair Folk”, and magic are all well attested; his A Vision presents a metaphysical system dictated to his wife George by “spooks”. The place of the occult among the Modernist poets Yeats, Eliot, Pound, and H.D. is a rich and living vein of scholarship. And more recently, the work of William S Burroughs is no less an exploration of ASC, magic, and other aspects of the paranormal; the novelist’s character Kim Carsons from The Place of Dead Roads embodies these fascinations well: “His mother had been into table-tapping and Kim adores ectoplasm, crystal balls, spirit guides and auras.” Such an offhand catalogue seems to both strengthen and overturn Kripal’s position: there is doubtless a longstanding and general interest and engagement in “the paranormal” among thinkers and artists, but, if this is so, then the humanities have always been, in a way, the superhumanities: just what institutional and societal changes, then, does Kripal imagine are called for?

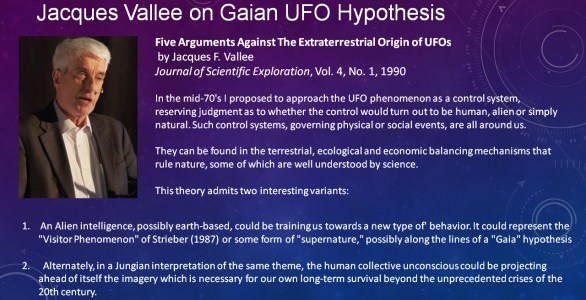

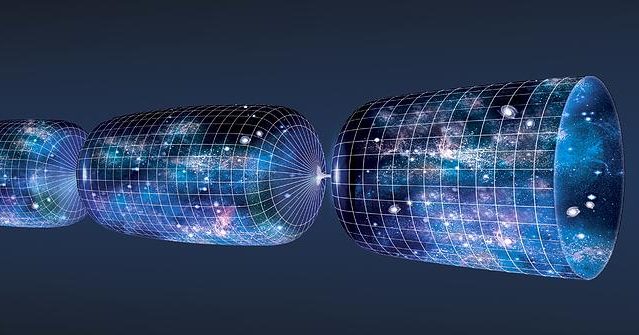

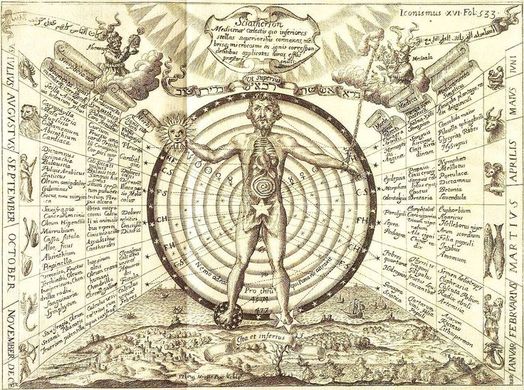

I wager this apparent tension can be resolved if we attend both to the explicit historical horizon Kripal is working within and some of its dimmer, more occluded edges. As I understand it, Kripal is pushing back against a certain understanding or reception of Weber’s contention that industrialized and bureaucratic societies undergo a “disenchantment” (German: Entzauberung) that gets restated in the Secularization Thesis in sociology, that this process of modernization witnesses a decline in religious belief and practice and perhaps its ultimate disappearance. Kripal sometimes seems to echo the too easy “refutation” of “the death of God” by those who point to the resurgence of fundamentalisms and the rise of New Age spiritualities. In my understanding, these theses concerning secularization can be true quite apart from flows and ebbs in belief, for they describe the advent of a certain horizon within which belief must now orient itself, namely that of a purely immanent reality, as opposed to a nature transcended by a supernatural realm, exemplified by that of the natural sciences. It is this context that lays the ground for the very possibility of the appearance of the paranormal as such, since, before, there was only the miraculous or supernatural. It is therefore no accident that Kripal begins his history of the occult superhumanities in the Eighteenth century. It is only when the supernatural has become questionable, its home in a divine Creation being replaced by a new normal, that defined by the Scientific Revolution and the consequent changes in our self understanding by developments in astronomy (the Copernican Revolution), geology (the earth’s being more than, e.g., 6,000 years old), biology (the theory of evolution), and even theology (demythologization), that the need for a category of the paranormal can even come to be felt. It is therefore somewhat beside the point to protest that this purely secular worldview is by no means absolute and that an interest in and engagement with the miraculous and paranormal persist. Indeed, I sought to even strengthen the argument against a certain strong reading of the Secularization Thesis, when I was graciously allowed to ask Kripal if he saw the post-secular (a disillusionment with purely secular answers to how we should live and the recognition that the resources of religious tradition have neither been transcended nor exhausted), contemplative studies, or psychedelic studies as dovetailing into his imagined project for a superhumanities. (Kripal’s response was negative).

It’s at this point a distinction between two senses of “materialist” becomes important. Kripal perceives, I take it, that the spirit of the time is essentially “materialist”: regardless of the religious beliefs of the populace, the reigning worldview is natural scientific (“only matter is real”), technological, and technocratic, evidenced by the valorization of STEM in higher education. The humanities, by contrast, have been forced into an ever tighter corner, both by these ex cathedra forces (philistine capitalism) and by their restricting themselves to various parodies of the natural sciences (e.g., attempting to develop empirical, testable methodologies) or to merely “negative”, critical stances. In this view, the Other to Kripal’s imagined superhumanities is just this secular, materialist episteme for which only the physical and objective, or anonymous, third-person perspective, is real and true. However, there is another sense of “materialist”, that found in the expression “historical materialist”, whose viewpoint is summarized neatly in Marx’s early statement that “It is not consciousness of [human beings] that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.” From this point of view, the ascendance of the secularism that displaces the religious and spiritual is not a “Mental Fight” (in Blake’s words) but a process better understood as related to wealth and power. The Age of Reason and its various atheisms didn’t arise because of some dialectic of spirit, some current in cultural conversation, but because of the decades of carnage wrought by religious wars in the wake of the Reformation, most notably the Thirty Years War. The natural sciences and the technologies they underwrite (and that later determine them) are not true because they are within certain contexts demonstrably so, but because they work; they fulfill the demand, in Jean-François Lyotard’s terms, that they perform, and under capitalism that performance is measured by profitability. It is no wonder, then, that STEM is valued and funded, but even those humanities whose results can be harnessed as means to ends of profit and power are also cultured: language departments that study the language of the moment’s enemy or psychology departments that help refine methods of enhanced interrogation… Kripal’s cultural adversary is not so much or only the “materialism” that identifies mental states with brain states but perhaps moreso the “materialism” of invested, social forces that values STEM for the power and profit these disciplines can bestow.

There is, more profoundly, a further distinction even more germane, I think, that between “meaning” and “meaning”. As Kripal outlines in opposing STEM to the humanities, the latter operate in an interpretive, hermeneutic realm of understanding, or “meaning”. STEM explains where the humanities understand. But Kripal, in his description of certain paranormal experiences, invokes, I argue, a different “meaning”, one more akin to the meaning granted by precisely life-orienting religious practice or philosophical belief or that experienced in a mystical state, whether spontaneous or entheogenic. It is precisely this meaningfulness that religion has traditionally addressed and that modern, secular society has no time for, pretending to grant every citizen a freedom of conscience in this regard while supplying only one real “material” possibility, consumption. But even this distinction, I don’t think, quite catches what Kripal is after.

If I understand him, he seems to want paranormal phenomena to be taken seriously, admitted to be as real as presently accepted natural phenomena and their nature and consequences for our conception of human being and nature to be investigated. His history of the humanities’ engagement with the paranormal intends to establish this as both an incipient and not unreasonable project. Because such phenomena are not strictly merely paraphysical, their study demands a kind of investigation both and neither natural scientific or hermeneutic (I remain uncertain on this point). The interdisciplinarity he sees demanded is based on the phenomena’s exceeding our present reduction of the mental to the material (in our “secular, material” worldview) or our failure to fundamentally grasp the mental and its relation to the material. The superhumanities are therefore just these superdisciplines that also open the way to conceiving of our own super-, rather than trans-, humanity (hence his preferred translation of Nietzsche’s Übermensch).

If my characterization of Kripal’s thesis is at all accurate, I have a number of reservations. First, the whole problem of matter and mind is posed in a conceptually coarse manner: it seems to rely on an essentially Cartesian distinction between two kinds of “stuff”, res extensa (physical, material stuff) and res cogitans (conscious, thinking stuff), a characterization of the problem that overlooks the more sophisticated descriptions and articulations of consciousness that begin with Kant and come down to more recent reflections by Dieter Henrich, Manfred Frank, and (perhaps) Markus Gabriel, a current of reflection not sufficiently appreciated by, for example, one of Kripal’s favoured thinkers in this department, Benardo Kastrup (such, at least, is my impression). Secondly, it strikes me as odd that Kripal, teaching in a university in Texas, seems not to remark a very vital community of believers in the miraculous, if not the paranormal, the various fundamentalist Christian sects in North America, with their firm belief in the immortality of the soul, visions, glossolalia, miraculous healings, possessions, and so forth. This group, along with its New Age cousin, is also characterized by a tendency to believe in the conspiracy theories that have recently disrupted political life in North America and public health measures globally. This broader and graver problem of an epistemic breach in Western societies, a loss of faith (!) in secular institutions, including (not always coherently) STEM, is not easily disentangled from a belief in or affirmation of paranormal phenomena, and it’s just such sociopolitical ramifications that call for serious, concerted reflection.

All that being said, Kripal’s project is broad and deep, articulated in nearly a dozen scholarly books, countless papers and presentations, and an entire career of research and teaching. What I remark here touches on a very restricted portion of that oeuvre. Nevertheless, I am moved to engage Kripal’s thinking in this lecture, both because it addresses matters of mutual interest and concern and because, if such matters are at all important, they demand to be taken with a certain seriousness, which is, at the very least, a gesture of intellectual, scholarly respect.

alternate dimensions have reported encounters with

alternate dimensions have reported encounters with

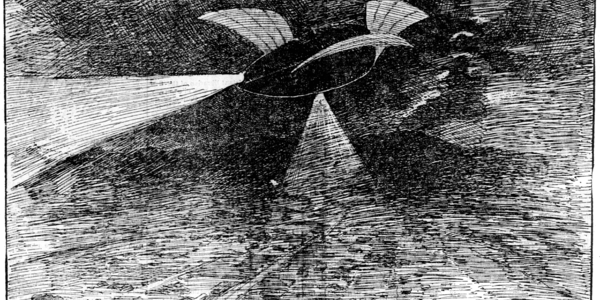

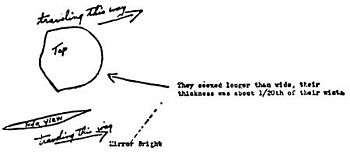

However, at the same time, he underestimates or discounts the popular culture presence of UFO and alien imagery preceding Arnold’s monumental sighting, as scholars and skeptics as diverse as

However, at the same time, he underestimates or discounts the popular culture presence of UFO and alien imagery preceding Arnold’s monumental sighting, as scholars and skeptics as diverse as

beliefs about human-extraterrestrial interaction and a Secret Space Program. However, in the same mouthful, he also swallows the line that Trump was recruited and placed in power by a group of “White Hats” working to unmask and destroy the “Deep State” (“

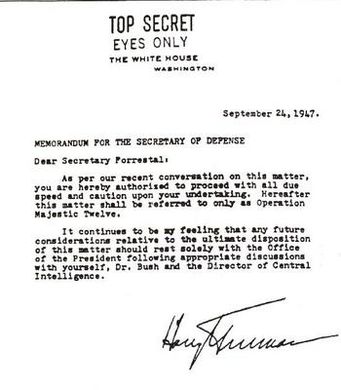

beliefs about human-extraterrestrial interaction and a Secret Space Program. However, in the same mouthful, he also swallows the line that Trump was recruited and placed in power by a group of “White Hats” working to unmask and destroy the “Deep State” (“ extreme right” had been growing in the decade leading up to Vallée’s expression of concern and was about to effloresce in the years following. Ufologically, an important set of rumours was begun, first thanks to Stanton Friedman’s groundbreaking research into the crash at Roswell in 1978, which was quickly followed by Berlitz’s and Moore’s 1980 The Roswell Incident. By 1984, the MJ-12 documents had surfaced, and, by 1988, an entire submythology had developed, about crashed flying saucers, retrieved and back-engineered alien technology, recovered ufonauts living and dead, treaties with alien races that traded technological know-how for the rights to mutilate cattle and abduct human beings, underground bases both human and alien, and the struggle to reveal this “horrible truth” that culminated in the TV documentary

extreme right” had been growing in the decade leading up to Vallée’s expression of concern and was about to effloresce in the years following. Ufologically, an important set of rumours was begun, first thanks to Stanton Friedman’s groundbreaking research into the crash at Roswell in 1978, which was quickly followed by Berlitz’s and Moore’s 1980 The Roswell Incident. By 1984, the MJ-12 documents had surfaced, and, by 1988, an entire submythology had developed, about crashed flying saucers, retrieved and back-engineered alien technology, recovered ufonauts living and dead, treaties with alien races that traded technological know-how for the rights to mutilate cattle and abduct human beings, underground bases both human and alien, and the struggle to reveal this “horrible truth” that culminated in the TV documentary

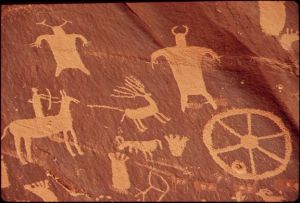

More importantly, the white supremacist sentiments that underwrite views about the inability of ancient, nonwhite peoples to construct monumental architecture spring not only from beliefs in European intellectual and technological superiority, articulated and entrenched in natural history and anthropology (race theory) but from the more deeply-entrenched technocentric / technophilic prejudices characteristic of European colonists, race theoretical hierarchies, and ufology in general, because it is the ideology of the so-called advanced societies.

More importantly, the white supremacist sentiments that underwrite views about the inability of ancient, nonwhite peoples to construct monumental architecture spring not only from beliefs in European intellectual and technological superiority, articulated and entrenched in natural history and anthropology (race theory) but from the more deeply-entrenched technocentric / technophilic prejudices characteristic of European colonists, race theoretical hierarchies, and ufology in general, because it is the ideology of the so-called advanced societies. The Nation of Islam’s founder, The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, makes of Ezekiel’s Chariot a wheel-shaped “Mothership”; his followers, therefore, have taken

The Nation of Islam’s founder, The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, makes of Ezekiel’s Chariot a wheel-shaped “Mothership”; his followers, therefore, have taken

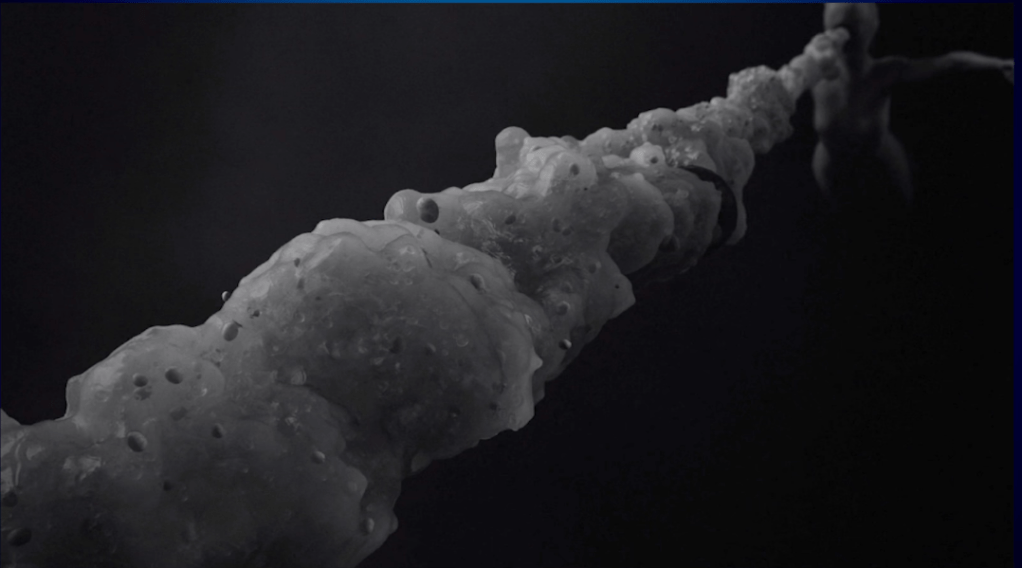

its plotting and its probing the relation between language and consciousness. Its first virtue is how the aliens resemble octopi or squid more than human beings.

its plotting and its probing the relation between language and consciousness. Its first virtue is how the aliens resemble octopi or squid more than human beings.  Even when this disguise is finally ripped off in the movie’s climax, the audience sees only an impersonal black form, as featureless as the liquid form is amorphous. By refusing to actually depict an alien, it employs a visual metaphor that is all the richer for its being nonliteral.

Even when this disguise is finally ripped off in the movie’s climax, the audience sees only an impersonal black form, as featureless as the liquid form is amorphous. By refusing to actually depict an alien, it employs a visual metaphor that is all the richer for its being nonliteral. The figure of the Mothman not only appears as a dark, indistinct, red-eyed menacing silhouette, but pareidolically as a mark on a car’s radiator grille, tree bark, and, most wittily, in a brainscan image.

The figure of the Mothman not only appears as a dark, indistinct, red-eyed menacing silhouette, but pareidolically as a mark on a car’s radiator grille, tree bark, and, most wittily, in a brainscan image. These latter imaginings share the strengths of those in Under the Skin and The Mothman Prophecies in being more suggestive than literal. As hybrid clones, the alien is as much a monstrous DNA as nonhuman being. The shapeshifting variety (however anthropocentric) wears its protean, unclassifiable Otherness on its sleeve, as it were. And the black oil combines alien-as-infection body horror, the fluid identity of the shapeshifter, and a metaphorical resemblance to petroleum ,all in a single, tour de force image.

These latter imaginings share the strengths of those in Under the Skin and The Mothman Prophecies in being more suggestive than literal. As hybrid clones, the alien is as much a monstrous DNA as nonhuman being. The shapeshifting variety (however anthropocentric) wears its protean, unclassifiable Otherness on its sleeve, as it were. And the black oil combines alien-as-infection body horror, the fluid identity of the shapeshifter, and a metaphorical resemblance to petroleum ,all in a single, tour de force image.

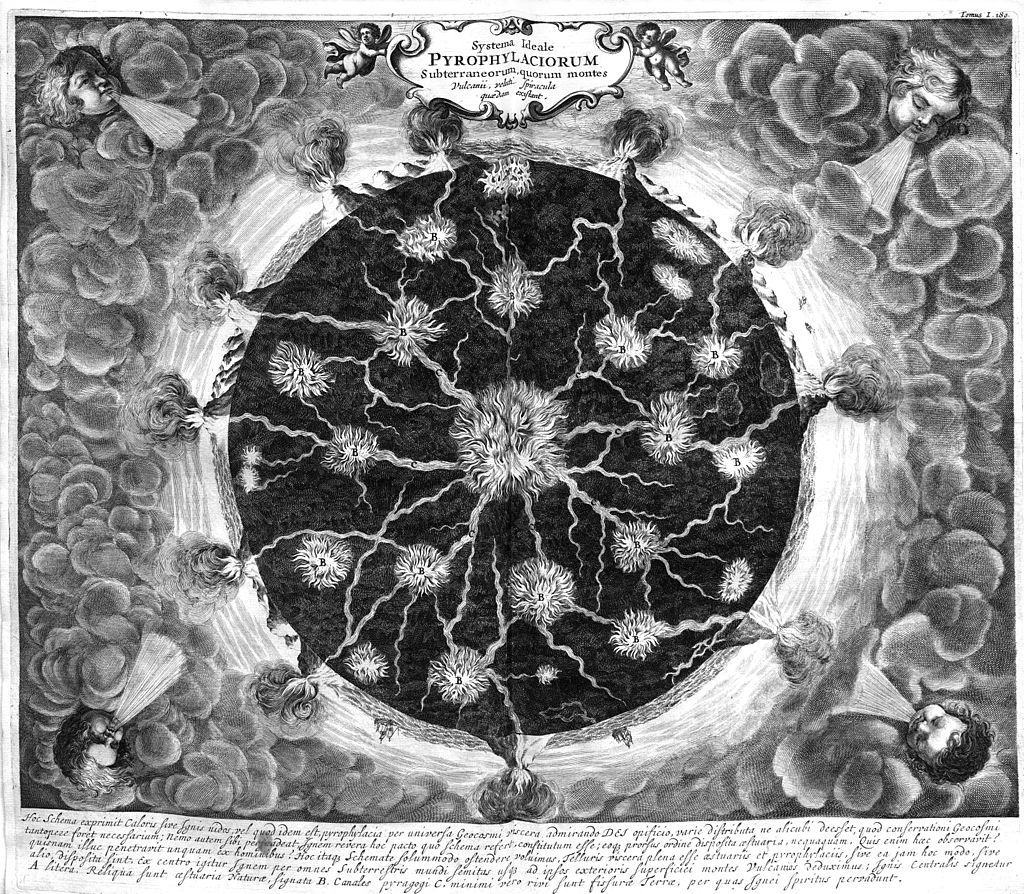

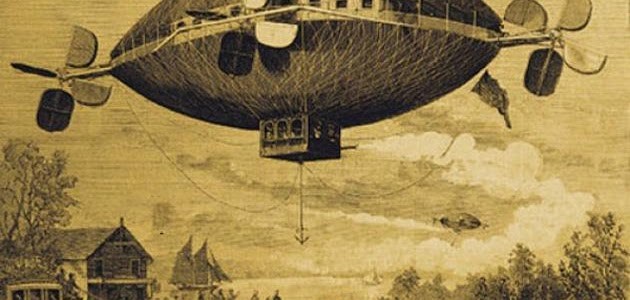

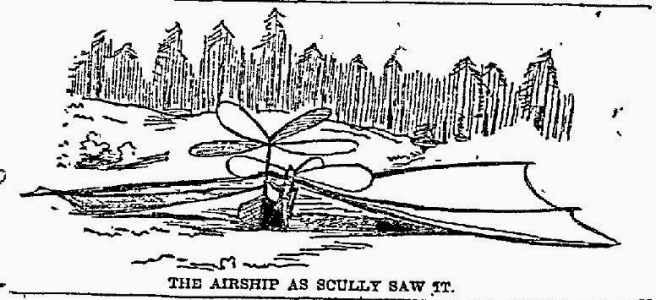

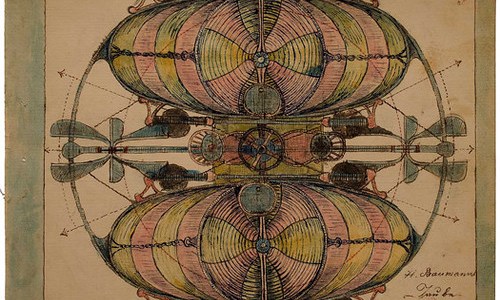

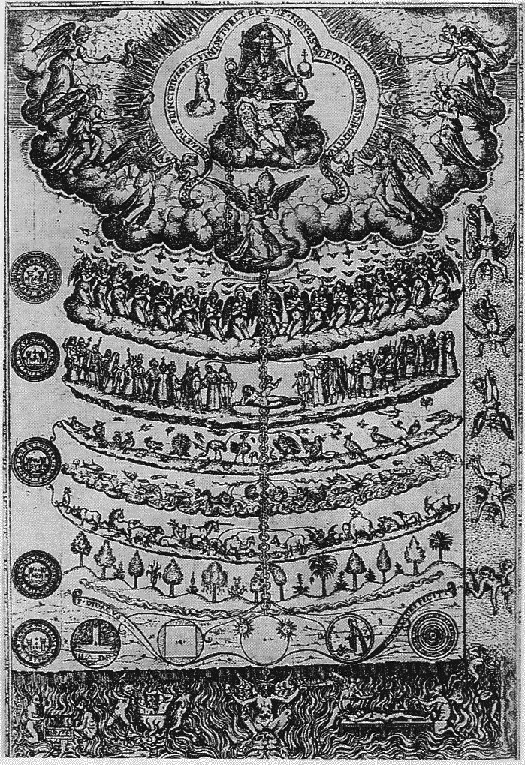

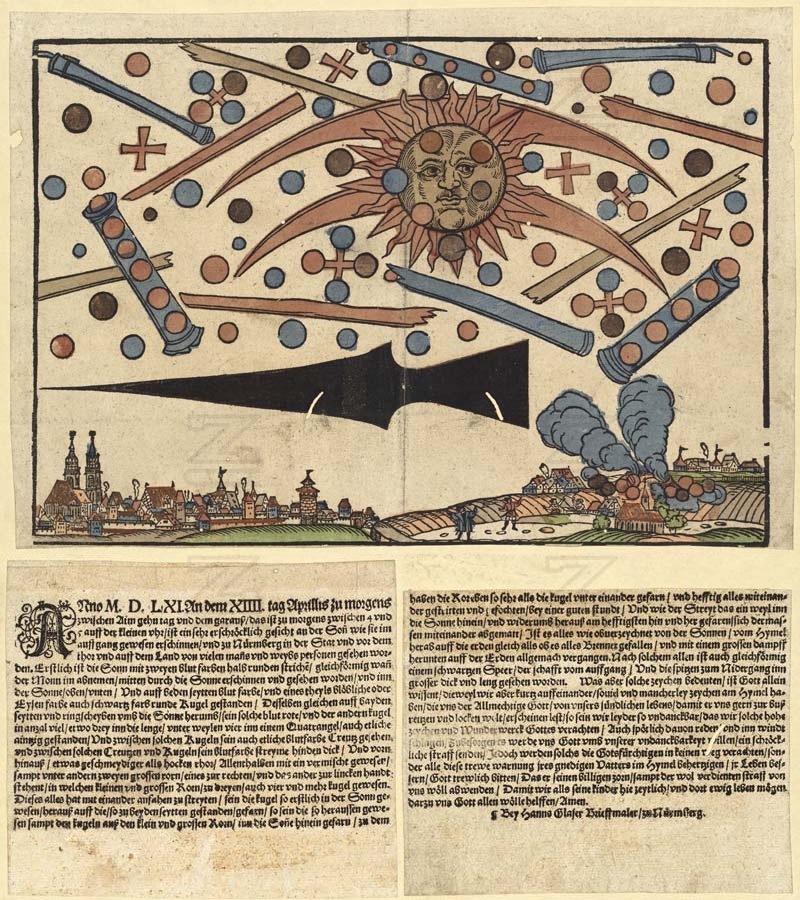

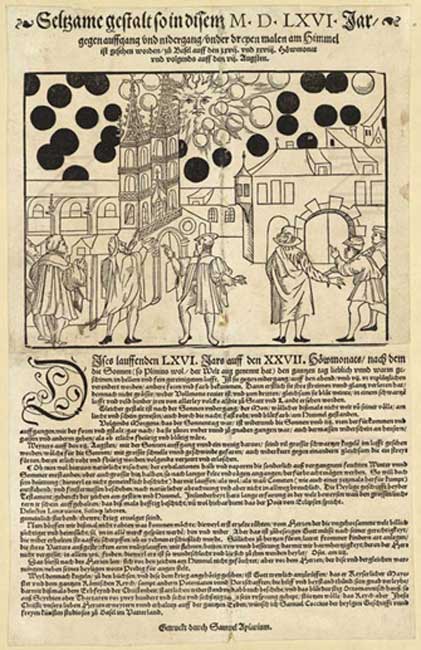

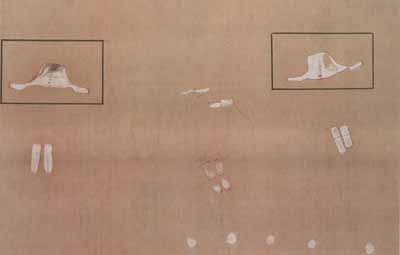

appeal made since the dawn of the modern UFO era (post-1947) in support of the claim that UFOs have been, in fact, a constant in human history. For example, Desmond Leslie in the book he wrote with George Adamski Flying Saucers Have Landed published soon after Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision eschews the freshly-minted expression ‘flying saucer’, preferring “to use the ancient names for the sky disks such as ‘car celestial’, ‘vimanas’, and ‘fiery chariots'” (14). Ancient Astronaut “theorists” refer also to ancient art, seeing there depictions of flying saucers and extraterrestrials.

appeal made since the dawn of the modern UFO era (post-1947) in support of the claim that UFOs have been, in fact, a constant in human history. For example, Desmond Leslie in the book he wrote with George Adamski Flying Saucers Have Landed published soon after Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision eschews the freshly-minted expression ‘flying saucer’, preferring “to use the ancient names for the sky disks such as ‘car celestial’, ‘vimanas’, and ‘fiery chariots'” (14). Ancient Astronaut “theorists” refer also to ancient art, seeing there depictions of flying saucers and extraterrestrials. and it was precisely the strikingly realistic manner of the then newly-discovered cave paintings of Altamira that gave an impulse to the visual arts at the beginning of last century, most famously perhaps in the work of Picasso. On the other hand, I’m unaware of any paleontologists inspired by the Odyssey to search for the remains of the Cyclops nor does anyone, to my knowledge, believe The Sorcerer of Les Trois-Frères to be a realistically-depicted humanoid. Indeed, this interpretive move parallels “literal” readings of the Bible that support the belief in the reality of a global inundation in the distant, mythological past. All these hermeneutics (interpretive approaches) err in the roughly the same way: they project a historically, culturally, and socially local communicative convention (namely, one of our own) onto human textual and artistic production in general.

and it was precisely the strikingly realistic manner of the then newly-discovered cave paintings of Altamira that gave an impulse to the visual arts at the beginning of last century, most famously perhaps in the work of Picasso. On the other hand, I’m unaware of any paleontologists inspired by the Odyssey to search for the remains of the Cyclops nor does anyone, to my knowledge, believe The Sorcerer of Les Trois-Frères to be a realistically-depicted humanoid. Indeed, this interpretive move parallels “literal” readings of the Bible that support the belief in the reality of a global inundation in the distant, mythological past. All these hermeneutics (interpretive approaches) err in the roughly the same way: they project a historically, culturally, and socially local communicative convention (namely, one of our own) onto human textual and artistic production in general.

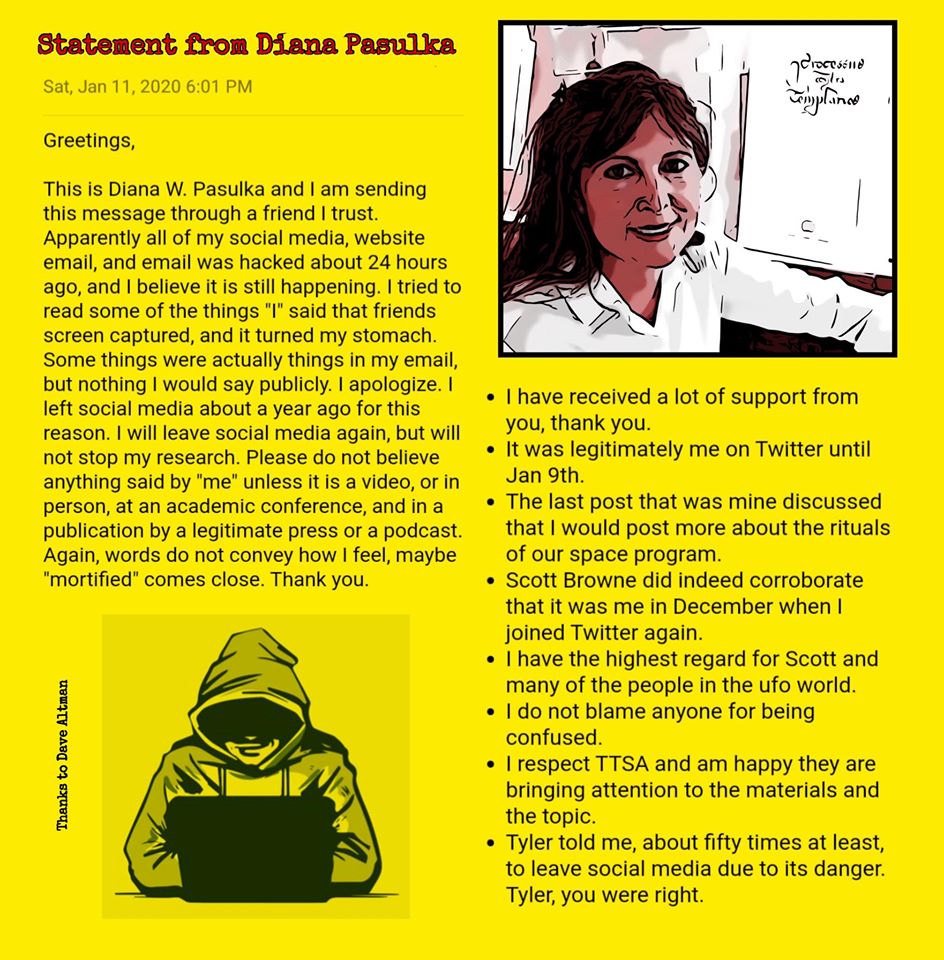

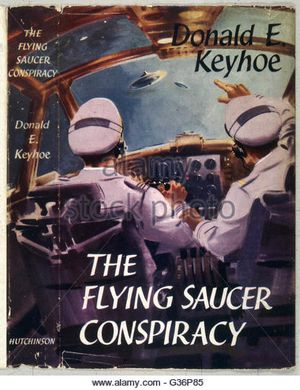

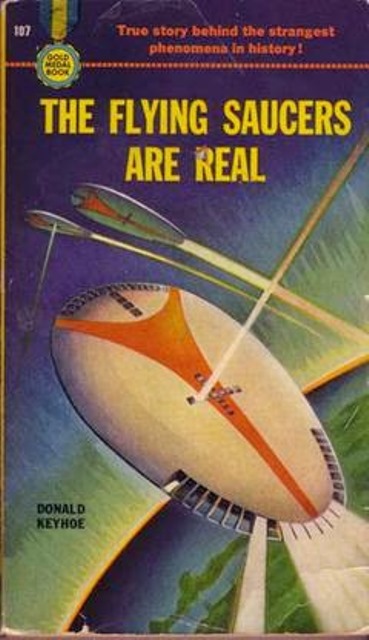

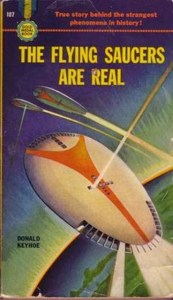

Hand in hand with this motif is that of the insider able to access this otherwise secret or tactfully unpublicized information, a figure that has morphed, today, into the whistleblower. Keyhoe, as an ex-Marine pilot, maintained many contacts within the military and government. Most of the narrative of his books is conversations he has with these inside sources. The final chapters of The Flying Saucers are Real find Keyhoe studying over two hundred secret Air Force files released to him and his petitioning a general of his acquaintance for the more than one hundred he had been denied! This figure with access to inside information undergoes a change as the official relation to the phenomenon (at least in its public guise) develops from secrecy, to debunkery, to indifference. The truth is no longer obtained via official documents from official channels, but via leaked or hacked documents or whistleblower,

Hand in hand with this motif is that of the insider able to access this otherwise secret or tactfully unpublicized information, a figure that has morphed, today, into the whistleblower. Keyhoe, as an ex-Marine pilot, maintained many contacts within the military and government. Most of the narrative of his books is conversations he has with these inside sources. The final chapters of The Flying Saucers are Real find Keyhoe studying over two hundred secret Air Force files released to him and his petitioning a general of his acquaintance for the more than one hundred he had been denied! This figure with access to inside information undergoes a change as the official relation to the phenomenon (at least in its public guise) develops from secrecy, to debunkery, to indifference. The truth is no longer obtained via official documents from official channels, but via leaked or hacked documents or whistleblower,  Here, the myth of the Nazi flying saucer, arguably first popularized by Holocaust denier

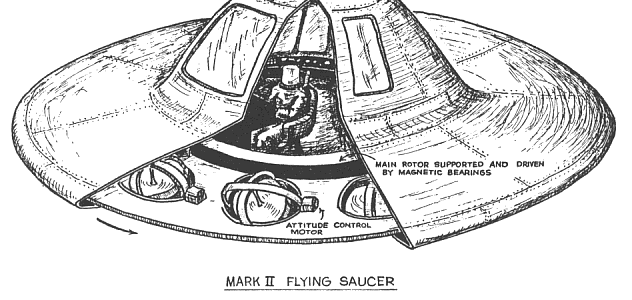

Here, the myth of the Nazi flying saucer, arguably first popularized by Holocaust denier

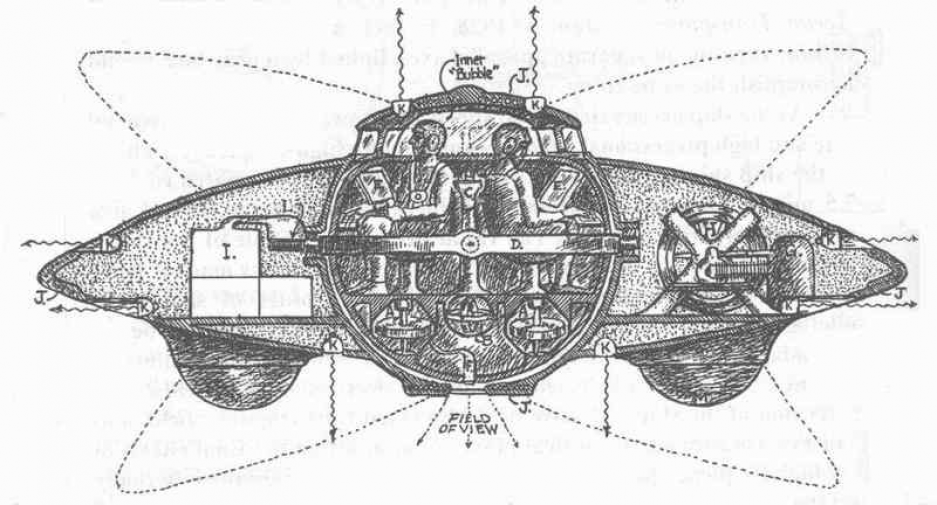

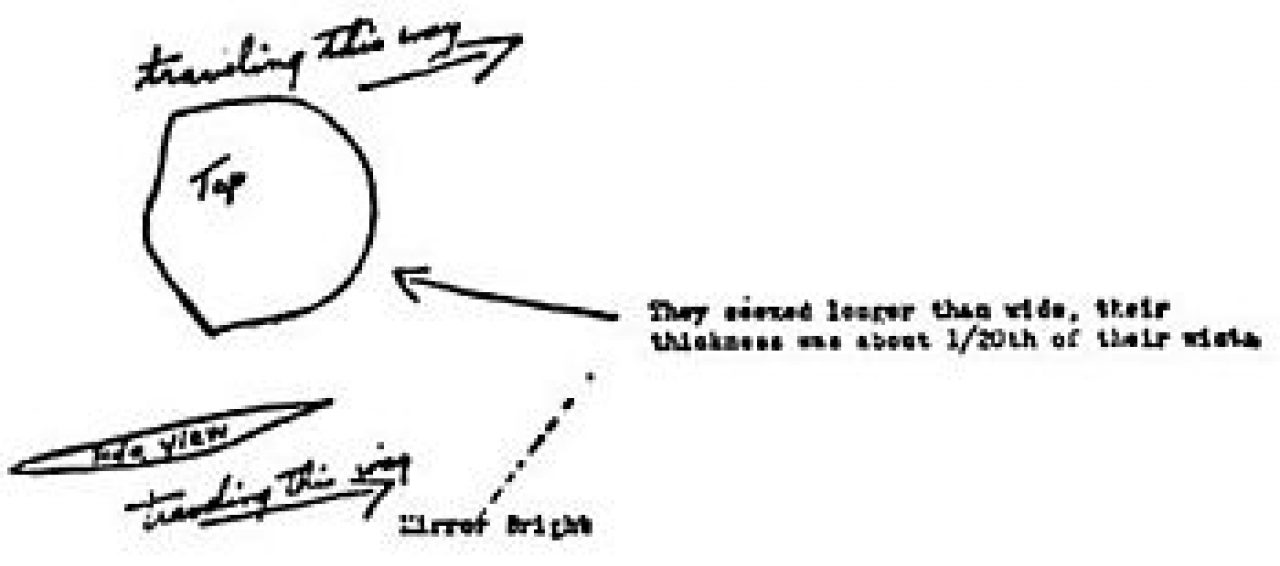

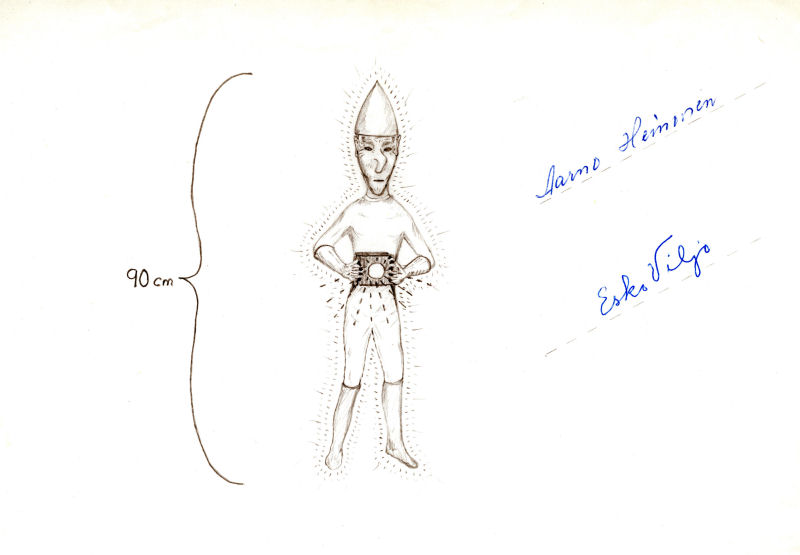

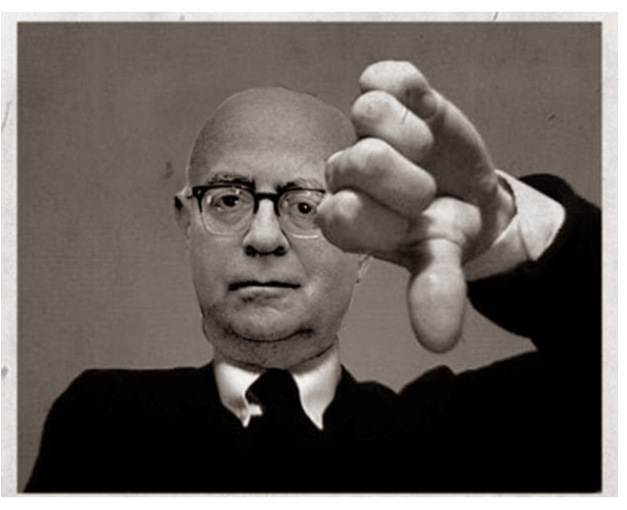

An important ufological popularizer of the ETH is Donald Keyhoe. In his first book, The Flying Saucers are Real (1950), he wrestles with the question of the origin of the flying discs. Having been pushed to the ETH by a process of elimination, he tries “to imagine how they [ETIs] might look” (136). Having read what he could of what we today call exobiology, he understands that there are “all kinds of possibilities.” Then, he makes a telling confession:

An important ufological popularizer of the ETH is Donald Keyhoe. In his first book, The Flying Saucers are Real (1950), he wrestles with the question of the origin of the flying discs. Having been pushed to the ETH by a process of elimination, he tries “to imagine how they [ETIs] might look” (136). Having read what he could of what we today call exobiology, he understands that there are “all kinds of possibilities.” Then, he makes a telling confession:

variety of topics from castle fortifications to folklore. Recently he has been exploring the confluence between consciousness, insanity and reality and how they are affected through the use of a wide variety of psychotropic drugs. His first novel, Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun, explores these issues to the backdrop of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd. He also writes a blog-site devoted to the mythology and reality of the faeries:

variety of topics from castle fortifications to folklore. Recently he has been exploring the confluence between consciousness, insanity and reality and how they are affected through the use of a wide variety of psychotropic drugs. His first novel, Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun, explores these issues to the backdrop of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd. He also writes a blog-site devoted to the mythology and reality of the faeries:

to be tight-lipped (when they have lips), but the Space Brothers of the Contactees and channelers are overwhelmingly loquacious. To tease out the politics from the communications received since the 1940s (and before, from the denizens of the Solar System encountered by Swedenborg, the various Ascended Masters of Blavatsky’s Theosophy?…) would demand the dedication of a team of dogged readers, which, luckily, would not have to start from scratch. There is already a small body of research, produced primarily by religious studies scholars. One example of an explicitly worked-out utopia, however, whose blueprint comes from the ETs who created all life on earth (according to their designated spokesman

to be tight-lipped (when they have lips), but the Space Brothers of the Contactees and channelers are overwhelmingly loquacious. To tease out the politics from the communications received since the 1940s (and before, from the denizens of the Solar System encountered by Swedenborg, the various Ascended Masters of Blavatsky’s Theosophy?…) would demand the dedication of a team of dogged readers, which, luckily, would not have to start from scratch. There is already a small body of research, produced primarily by religious studies scholars. One example of an explicitly worked-out utopia, however, whose blueprint comes from the ETs who created all life on earth (according to their designated spokesman

In the Alien Abduction literature, the ETs are often described as being insectoid in various ways, and the figure of the Mantis is prevalent. So, in the context of the development of the myth (if not the hard core of the mystery), Heard’s book is, intentionally or not, significant.

In the Alien Abduction literature, the ETs are often described as being insectoid in various ways, and the figure of the Mantis is prevalent. So, in the context of the development of the myth (if not the hard core of the mystery), Heard’s book is, intentionally or not, significant.