Today, I share the closing three cantos from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery. These concern themselves with the rising tensions and paranoia before the outbreak of The Great War, the aerial bombardment of London by German zeppelins, and the myth of Hill 60 from 1915.

Tag: Phantom Airships

Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 18, 19, 21, 24, and 26

Today, the penultimate instalment of cantos from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, dealing most notably with perhaps the first cattle mutilation story (a hoax!) and an even more provocative tale that echoes one from the Middle Ages. This last had me scratching my head for a while, until I happened upon the explanation, looking into those Medieval stories of ships in the skies.

Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16

Today, the next instalment of cantos from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, here those dealing with five more days in April, 1897: further sightings, debunkings, newspaper articles, landings and encounters with naked, blond aliens decades in advance of George Adamski’s, an event reminiscent avant le lettre of the Maury Island incident, and even an aquatic sighting and encounter on Lake Erie…

Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: April 1, 2, 9, and 11

This fourth instalment from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery presents the opening cantos from the central section, focussed on the events of April 1897.

Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery: “The Phantom Airship”

Here, the third instalment of pieces from Orthoteny, a booklength poem on “the myth of things seen in the sky.” The first can be read and heard here. The second is the opening section of the chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery. Following that Prelude is “The Phantom Airship,” another nine cantos that recount salient sightings and reactions, which, in their turn, lead into the momentous month of April, the topic of the poem’s next section(s).

Orthoteny: from a work in progress: from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, “Prelude”

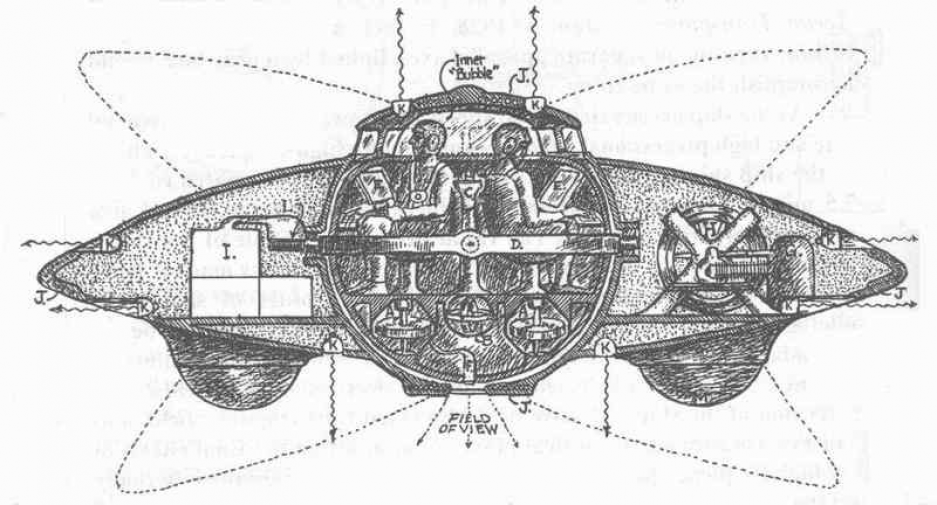

One of the most complete, if unfinished, parts of the work-in-progress was composed quickly after the project was begun. I took extensive notes on the Phantom Airship wave of 1896/7 from all those UFO books I had obtained to that point and rendered them poetically. These texts are woven from certain leitmotifs: triads, the colour blue, and other recurrent details. It is this coherence I was eager to show, if not refer to explicitly.

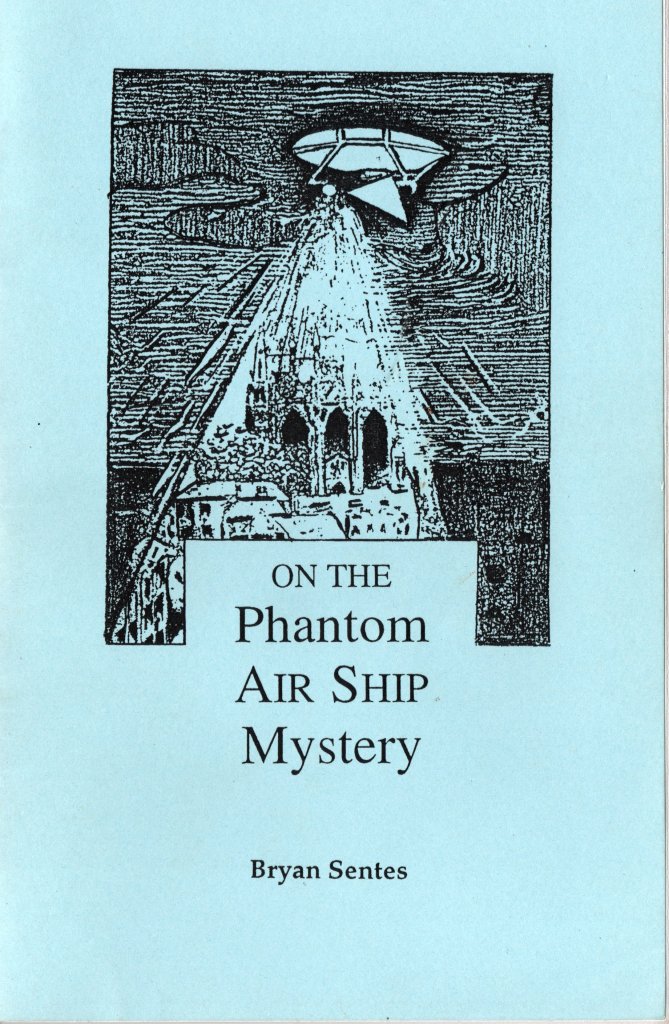

On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery was originally published as the chapbook On the Mysterious Airships in 1995. I had the opportunity to perform the Prelude at multiple readings in Europe in the summer of 1996, the most memorable being at the Stromlinienklub in Munich before an audience of over 500.

It remains uncertain whether this part of the epic will remain the same in the completed work. It is, after all, and may perhaps remain, as the epigraph says, “…a blueprint, a mock-up, a prototype…”

Alexander Hamilton’s Prototypical Cattle Mutilation Tale

Over at Mysterious Universe, Brent Swancer shares a collection of premodern tales of cattle mutilation, among them the prototypical if not archetypal story told by Alexander Hamilton during the Great Airship Mystery of 1896/7. Spencer’s reminding us of this report opens the door to my sharing my own poetic rendering of the encounter, one of the many smaller poems that compose a long poem On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery, part of that larger, “epic” project whose working title is Orthoteny.

Since WordPress does violence to the lineation of poetry, I post the poem, below, as a PDF.

Anchored in philology: an addendum to “When a sighting report is not”

The latest example of Rich Reynolds’ irrational tenacity sent me to Aubeck’s and Vallée’s Wonders in the Sky. For all its failings, catalogued at length by at least two tenacious critics and admitted by no less than Vallée himself, the book is not without its saving graces.

I was recently moved by being shown John Carey’s study of sky ship tales from medieval Ireland to use his scholarship to make an argument about the interpretive dangers of reading narratives from distant times and cultures. At the time, I went to Wonders in the Sky and was surprised I could find no mention of these sky ships. It turns out Aubeck and Vallée were one step ahead of me in this regard, however.

I was unable to find such stories among the 500 they present in their “Chronology of Wonders”, because they include them in the second section of illustratively questionable tales, “Myths, Legends, and Chariots of the Gods”. The authors base their own analysis (pp. 405-11) on Carey’s, noting both the scant references to the sky ships in the annals and the increasing embellishment of the basic story line over time.

Most impressively (to me) they resolve the mystery of how the most famous (and fabulous) version of the story, wherein the sky ship’s anchor is caught in the church’s door arch, is repeated during the Phantom Airship flap of 1896/7: according to Aubeck and Vallée, the Boston Post published an article “A Sea Above the Clouds: Extraordinary Superstition Once Prevalent in England” that recounted two British folktales, one a version of the more famous Irish one. Two weeks later, the story was updated to the present and relocated to Merkel, Texas as reported the Houston Daily Post 28 April 1897, two days after the incident was said to have occurred (p. 409).

A (very) little more digging turns up that the article Aubeck and Vallée refer to also appeared (seemingly for the first time) in the 7 March 1897 edition of Utah’s Salt Lake Tribune and the next day in the Nebraska State Journal. It remains nevertheless no less astounding, however, that so recherché a philological tidbit should make the rounds as a syndicated article of all things in America’s newspapers at the time!

To paraphrase Chaucer: The life so short, the bookshelf so long to read!

When a sighting report is not

Visitors to tha Skunkworks will know how little patience I have for those (whose name is legion) who insist on taking premodern tales or artwork to be the equivalent of modern-day UFO sighting reports. I’ve taken Vallée to task for conflating alien abduction reports with fairy tales and Velikovsky, Jaynes, and Ancient Astronaut theorists (not to mention even scholar D. W. Pasulka, who should know better) for their no less ahistorical errors. My point has always been that the way we communicate today differs from the ways of other times and places (linguists would refer to differing “codes”), and, so, it’s just ignorant to read texts or interpret art universally according to how we write and represent things here and now. Friend and Irish Studies scholar Antoine Malette has provided me with an excellent case in point.

Celtic Studies scholar John Cary (presently at University College Cork) presented a paper in 1992 titled “Aerial Ships and Underwater Monasteries: The Evolution of a Monastic Marvel” (interested readers without access to JSTOR can sign up for a free membership to read it, here). In his study, Cary scrutinizes variations of a story familiar to readers of Jacques Vallée’s Passport to Magonia (144). In Cary’s version:

There happened something once in the borough called Cloena [=Cionmacnoise], which will also seem marvellous. In this town there is a church dedicated to the memory of a saint named Kiranus [=Ciarán]. One Sunday while the populace was at church hearing mass, it befell that an anchor was dropped from the sky as if thrown from a ship; for a rope was attached to it, and one of the flukes of the anchor got stuck in the arch above the church door. The people all rushed out of the church and marveled much as their eyes followed the rope upward. They saw a ship with men on board floating before the anchor cable; and soon they saw a man leap overboard and dive down to the anchor as if to release it. The movements of his hands and feet and all his actions appeared like those of a man swimming in the water. When he came down to the anchor, he tried to loosen it, but the people immediately rushed up and attempted to seize him. In the church where the anchor was caught, there is a bishop’s throne. The bishop was present when this occurred and forbade his people to hold the man; for, said he, it might prove fatal as when one is held under water. As soon, as the man was released, he hurried back up to the ship; and when he was up the crew cut the rope and the ship sailed away out of sight. But the anchor has remained in the church since then as a testimony to this event.

Curiously, Vallée (and Donald B. Hanlon from whom he cites the story (and Harold T. Wilkins, Hanlon’s ultimate source)) remarks the tale’s variations from eighth century Ireland to Merkel, Texas in April, 1897 and (along with Hanlon) the provocative if no less problematic analogues between the medieval and modern versions but neglects to unfold the implications of this variation, unlike the scholar Cary.

All in all, Cary examines no fewer than six versions of the story, including the newspaper report from 1897. He summarizes their development as follows:

(a) In the mid-eighth century, a notice that ships had been seen in the air was included in the annals. The apparition was subsequently localized at the assembly of Tailtiu, and said to have been witnessed by the then reigning king of Tara.

(b) By the late eleventh century the story had been transferred to the reign of the tenth-century king Congalach Cnogba, and embellished with the detail of the lost and recovered fishing-spear [thrown from the ship]; there was now only one air ship,

(c) By the end of the twelfth century the story was shifted to the monastic milieu of Clonmacnoise, and an anchor took the place of the fishing-spear.

So, the version Vallée and Hanlon compare to the 1897 newspaper story is already so embellished it can’t be seriously considered anything other than a fanciful (i.e. fictional) tale of the marvelous (a medieval genre with its own features and purposes). But I’m not interested in the tiresome exercise of merely debunking Vallée et al. The philology of this tale’s development is more complex and interesting in its implications.

Having surveyed the tale’s variations, Cary conjectures about how it might have arrived at its final, thirteenth century version. The sky ship’s anchor getting caught echoes a motif from around the world and from at least two extant Irish texts, the saga Tochmarc Emere and an extended gloss on the hymn “Ni car Brigit buadach bith“. The tale reaches its fullest elaboration with the Clonmacnoise version likely because, as Carey writes, “Clonmacnoise in the later Middle Irish period seems to have been greedy for marvels: quite a number of little tales, drawn in all likelihood from many disparate sources, associate the monastery with fantastic occurrences of all kinds.” Therefore, Cary concludes, “it seems likeliest that it was in the heady atmosphere of Clonmacnoise mirabilia-collecting” that previous versions and other material “were fused into a single tale.”

The very scheme of the story (aerial ships) and other marvelous elements woven into it by the monks of Clonmacnoise are part of a larger tapestry in Irish and world literature. Cary cites the example of “the famous encounter between the mortal Bran in his ship and the divine Manannán in his chariot, and the [ancient, pagan] poem in which the god declares that what is sea to one is land to the other”. Cary proposes that

such flourishes of paradox and surreality subordinate our habitual frame of reference to an alien [!] and unreckonable scheme which lies beyond it. The stories, in [Proinsias] Mac Cana’s words, explore “the relationship between the natural and the supernatural, between this and the other world, together with the ambiguities and relativities of time and space which were implicit in their interaction.”

Cary’s and Mac Cana’s point here is all the more persuasive when one reflects that the clouds’ being compared to the foam of the sea is ancient, and the revery that inspires it is likely one many of us will remember from our childhood.

However much the story of sky ships is caught up inextricably in daydream, poetic inspiration, and embellished retellings, the matter is still more complex. As all authors here—Cary, Vallée, and Hanlon—admit, the problem of how the modern, newspaper story follows so closely upon the thirteenth century version cited above is “a recalcitrant one.” Moreover, Cary, being the sincere scholar he is, admits up front that

the date, the range of attestation, and the fact that the item [the appearance of aerial vessels] was first recorded in Latin all suggest that we have here to do with a contemporary notice of an anomalous occurrence [my emphasis]. We will of course never know what it really was which some person or persons saw overhead in the 740’s, or how many retellings and mutations separated the first testimony from its distillation in the annals.

In the case of the newspaper story from the Houston Daily Post, the story either records a real event, copies the tale from the thirteenth century Norse text Konungs Skuggsj, or uncannily draws from the same sources of inspiration that coalesced in that version; each of these possibilities equally strain credulity. More to the point, we’re still left with the mystery Cary notes, “what it really was which some person or persons saw overhead in the 740’s.”

Those inclined to believe the Psychosocial Hypothesis will maintain that even those earliest, lost passages from the annals record nothing more than rumours, themselves merely stories like that of Bran and the god Mannanán, inspired by the same imaginative schema as the Irish poem. But this response, ironically, commits the same error as taking all stories to be equivalent to witness reports, conflating the genre of the annal or chronicle with that of mirabilia, forgetting that Herodotus called his writings “histories” motivated by the meaning of the ancient Greek verb at the root of our word ‘history’, meaning to inquire, explore, or, as the poet Charles Olson so forcefully put it, to see for oneself. This is to say, no less ironically (or dialectically) that Herodotus’ histories and medieval annals and chronicles are closer in spirit and linguistic code to modern day witness or newspaper reports than the marvelous tales worked up the monks of Clonmacnoise. And a sufficiently persuasive account for how the 1897 version of the story came to be written is still wanting.

Thus, a further irony leads us to a notion central to Ancient Astronaut theorizing, that the body of literature under scrutiny here, like all those myths such theorists point to, is the pearl formed by the oyster of the Unconscious or Creative Imagination around the hard grain of truth of “what it really was which some person or persons saw overhead”. But this proposal doesn’t get us very far either, for just what the medieval annals record, in this case, at least, is lost, and, ironically (…), the modern-day version is, in Hanlon’s words, all the more “strange and, in fact, downright suspicious” precisely because of its mirroring the thirteenth century, demonstrably fabulous version.

What should remain beyond a reasonable doubt is the need for and value of the application of intelligent, sensitive specialized erudition in such matters, an application neglected by all the ufological authors in question. Just how to understand temporally and culturally distant narratives concerning anomalous aerial phenomena, let alone nonhuman entity encounters, is no simple matter. Indeed, similar scrutiny can be applied even to the hermeneutics, productive and receptive, of modern-day witness reports, as if their being contemporary makes them any more immediately comprehensible. By a further turn of the screw of irony, such considered and well-informed analyses and explanations render the topic all the more mysterious, leaving as well the hard kernel of the mystery of just what was seen along with the strangeness of its apparent transhistorical consistency as further grist for the mill of reflection, investigation, and speculation.

Phantom Airships, after the fact

Recently, a commenter at UFO Conjectures felt the need to share with me a link concerning mystery aircraft, from 1865-1946. I was a little taken aback, as I’ve been well-apprised of this history since beginning my work on Orthoteny in the early 1990s.

The 1994 chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery cuts about the same swath, focusing on the Phantom Airships of 1896/7, then jumping ahead to the years just before the Great War, ending with the first bombing of London by Zeppelins and the story of Hill 60, before punctuating the section with the first modern sighting, Kenneth Arnold’s, in 1947.

I therefore share today the final three poems from the Phantom Airship sequence proper.

1913

The luminous object witnessed early last evening

The War Office has declared a spy-craft

Tonight a piercing light

lit up every corner

swept up to the hills

Bright lights flew over at thirty miles an hour

huffing like a faint train

the squeal of gears a clank of flaps

Rising last evening

all of magnitudes greater

than Venus

Before daybreak

unidentifiable lights

crossed the Channel

Seen overhead

sixty miles further

every hour after

All afternoon

they cruised west in threes

streets crowded to see

With sunset

one’s lamp played down

gone in a flash

From the east

three came

to hover an hour

Silhouetted

in their own

dazzling glare

Zeppelin

The tram stops

Blackout

A distant drone

The audience rises

To sing

“God Save the King”

One incendiary

Crashed through the ceiling

Went off in the hall

They were in bed and old

Knelt by the bed

And held each other

Another fell between the roofs

Onto the narrow lane just in front of them

But bounced off before it burst

The side of one house

And the Salvation Army Barracks windows

Blown out

A boarding house burned down

The Butcher’s shutters rattled

Neighbours in sheets on the street

Three of them lit up against the sky

Incendiaries fireballs falling

Searchlights and the city burning making a twilight

Hill Sixty

Dawn broke clear over Sulva Bay

Only six oval silvery clouds loafed

Undisturbed by the breeze

At sixty degrees

To us twenty-four

Six hundred feet away

Over the Hill a gunmetal cloud

Three hundred feet high and wide nine hundred long

Not nineteen chains from the trenches

The First

Fourth Norfolk

Ordered to reinforce the Hill

Were lost to sight as they marched

Into the cloud

For almost an hour

It rose then

Off with the others

North

No trace

Or record of them

Every found

Rime & Confirmation: two excerpts from Orthoteny (w.i.p.)

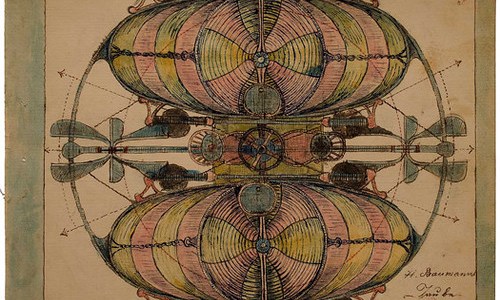

The motivation behind all the work here in these Skunkworks is the composition of a version of that “modern myth of things seen in the sky”, whose working title is Orthoteny. That title is taken from the ufological writings of Aimé Michel, specifically his Flying Saucers and the Straight-line Mystery (1958).

Within the texture of the poetic work, such straight lines are the rimes or repetitions between parts of the myth or that connect the myth to the wider field of human culture. Within the phenomenon itself, such repetitions of shape, behaviour, and other features are taken as confirmation of the objective reality of UFOs and the entities associated with them. Such echoes are also often adduced as evidence the phenomenon has been a constant in human history. Ufologically, I am vigilantly critical of such ahistorical thinking, but in the context of the mythopoetic work they lend the theme vista.

As an example, I post two excerpts from the work-in-progress. The first is the fourth section of the poetic sequence, Magonian Latitudes, from my 1996 trade edition Ladonian Magnitudes, concerning the Thirteenth century story of a cloud ship whose anchor got caught in the door arch of Saint Kinarus’ Church, Cloera County, Ireland. (Irish poet and Nobel Prize laureate Seamus Heaney treats the same theme in the eighth section of his poem “Lightenings” from his 1991 collection Seeing Things). The second is from a section of my chapbook On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery (1995), “The Phantom Air Ship” that concerns an analogous story, this time from Merkel, Texas, in 1897.

[from Magonian Latitudes]

A marvel in Cloera County

interrupted Sunday Mass

It befell an anchor on a rope

caught in Saint Kinarus’ door-arch

Where the line ended in clouds

the congregation saw some kind of ship

One crewman dove and swam down

as if to free the flukes from the keystone

But they seized and would hold him

but that the Bishop

On grounds terrestrial air

may well drown one celestial

Forbade it

and freed

Quick as limbs can swim he rose

to hands on ropes and ladders

The anchor rang and cut

the line coiled down about them

[from On the Phantom Air Ship Mystery] 26 April [1897]

Sunday in Merkel church-goers returning from evening service saw a dragging along the ground

Followed it bounce onto the tracks and catch a rail

A light ship’s anchor roped high up to a lamp brighter than a locomotive’s

And lit gondola-windows of an air ship

After nine minutes a small man in a cobalt blue jumpsuit

Came down the line to look things over and cut it

Skunkworks on Kevin Randle’s “A Different Perspective”

I had the honour and pleasure to be a guest on Kevin Randle’s podcast “A Different Perspective”.

We discussed all the things wrong with History’s Project Blue Book, the uncanny parallels between the Phantom Airship flap of 1896/7 and the post-1947 modern era, all that’s spontaneously literary about the history of UFOs, and the enduring, “hard kernel” of the mystery.

You can hear it all here.

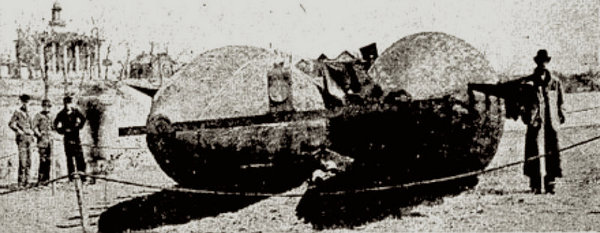

Phantom Airship Crashes at Jefferson and Aurora

Since this year’s Solstice, Kevin Randle has been writing on the purported crash of an airship in Jefferson, Iowa in April 1897, providing a wealth of original material and even a photograph of an airship that landed in Waterloo, Iowa. He has gone on to contrast this story with that of the other, more famous, crash in Aurora, Texas the same month.

Randle concludes that both stories are hoaxes, perpetrated by the newspapers of the day to increase circulation. Of course, from the point of view of the mythos, what is important is that the waves of both 1897 and 1947 present with what Leonard Stringfield would term “Crash/Retrieval Syndrome”. Indeed, what is most valuable from a textual point of view is that, as Randle notes, the debris from the Aurora crash were dumped down the town’s well, which links the tale, at the level of the signifier, to that most famous crash/retrieval story, that of Roswell, i.e. Rose-well, a name that will bring to the minds of some readers the expression “sub rosa“…. ‘Aurora’, too, is a more suggestive name than ‘Jefferson’ in this context, as well.

For these. and other very likely contingent, reasons, my initial poetic treatment of the Phantom Airship Mystery includes the crash at Aurora, which I include below:

17 April: Aurora

The railroad passed

An epidemic just

The West Side burned down

Weevils got the cotton

*

One came in from the north low over Wise County with the sun

Ten twelve miles an hour dropping toward the ground

Clear over the square right at Judge Proctor’s windmill

Three miles away they saw the flash and explosion

Fragments over three acres east and northeast

Windmill and watertank wrecked

flowerbeds ruined

What remained of a small man disfigured past human resemblance

And his hieroglyphic log penned in violet

Together were buried in the cemetery that day

*

I was in school that day and nothing happened

He saw the air ship when it swung in low to crash

They wouldn’t let me see it but told me all about it

They went to the crash and saw the wreckage and torn-up body

I heard about it all my life

It passed like any other story

In the Masonic Cemetery no unmarked graves

Never was a windmill at the Judge’s

Tons of metal found by the son down the well years later

Back to the Skunkworks

Just last week, a friend recently publicized a chapbook of mine composed and published  over twenty years ago, and the response, livelier than any to any of my work in recent memory, encourages me to return to the work that chapbook began.

over twenty years ago, and the response, livelier than any to any of my work in recent memory, encourages me to return to the work that chapbook began.

I shouldn’t be surprised, in a way. This poem was the center-piece of the performances I gave during a tour of Germany in 1996, and then, too, the response was gratifying: one audience member excitedly came up to me to say he would buy everything I would publish, and a friend I made during that tour, the German novelist Georg Oswald, approved with pleasure the approach I took to the material. And a few years later this sequence was well-received by Terry Matheson, a professor of English who has applied narratology to alien abduction reports and who was kind enough to even teach the poem below in one of his classes.

So, for interested parties, I append one of the first poems from this project, the last poem of my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems. and return to back-engineering this “modern myth of things seen in the sky”.

So, for interested parties, I append one of the first poems from this project, the last poem of my first trade edition, Grand Gnostic Central and other poems. and return to back-engineering this “modern myth of things seen in the sky”.

Flying Saucers

Tuesday three in the afternoon 24 June 1947

Kenneth Arnold of Boise, rescue pilot, businessman, deputy sheriff and federal marshal, U.S. Forest Serviceman

At 9,000 feet crystal-clear conditions

Alone in his Callair between Chehalis and Yakima

An hour’s detour searching for a lost transport

Out of the blue a flash like just before a midair crash

Made him look left north of Mount Rainier

To see at ninety degrees

Nine seeming jet planes in a V pointed south

The echelon vaguely bobbing and weaving

Flashing reflections

Twenty-four miles off

Against Rainier’s snows, tailless—

Flying nearly forty miles

Between Mounts Rainier and Adams

Three times the speed of sound

The first crossed the ridge bridging the mountains

As the last came over its north crest five miles back

Nine crescents needing to be

Half a mile long to be seen

Flying that fast that far away

So smooth mirroring sunlight

Like speedboats on rough water

Wavering in formation

Like the tail of a Chinese kite

Wings tipping flashing blue white

Each like a saucer skipped over water