Friday 3 October 2025 the Society for UAP Studies presented a colloquium with Professor Jörg Matthias Determann on UAP in the Muslim world. Determann’s presentation (about which I may have more to say when the Society shares it on its YouTube channel) was wide-ranging and often fine-grained. As anyone moderately informed would have guessed, Determann remarked how the UFO phenomenon has been interpreted in relation to the Arabic figure of the Jinn. Just as Jacques Vallée and others attempt to draw parallels between modern UAP sighting and entity encounter reports and what Evans-Wentz famously called “the fairy faith,” so commentators in the Arab world understand the UAP phenomenon as a modern-day encounter with the Jinn. But what concerns me here is a not-unrelated exchange that occurred in the post-presentation conversation (and continued between myself and another participant via email). The thesis proposed (after some helpful added articulation by moderator Mike Cifone) was that, in light of the modern “Phenomenon,” religion is revealed to be (however obscurely) the story of human interaction with occult (i.e. mysterious) Non-Human Intelligences. In what follows, I sketch out (or essay, drawing on the root of the word) the profile and ground of this notion of religion…

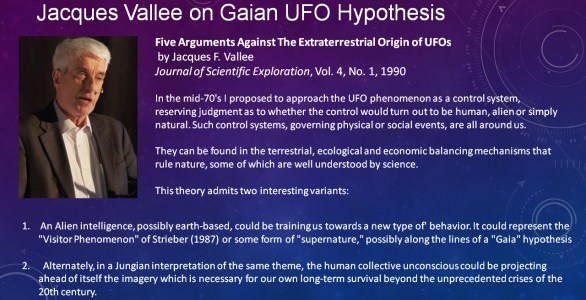

This view is generally attributed to Jacques Vallée’s Passport to Magonia (1969), which modifies if not develops the Ancient Astronaut literature that explodes at the same time Vallée’s book appears (however much the Ancient Astronaut “theory” goes back to the first appearance of Flying Saucers). For writers such as (most famously) Erich von Däniken, the gods of the premodern world were all primitively-apprehended extraterrestrial visitors. Vallée’s thesis runs deeper, in a sense, seeing all these (gods, angels, daimons, fairies, extraterrestrials…) as different appearances of one species of crypto-entity, a position later modified to propose that these same entities may themselves be only illusory products of an even more cryptic agent, merely elements of a Control System. (One might wonder how much of Vallée’s thinking here springs from the French anticlericalism he was raised in…). However much Passport consistently fails to make its case (as a vigilant close-reading reveals), its main contention has proven to be and remains influential.

I find this view of religion to be unsupportably literalist and reductive, and I am earnestly puzzled to see scholars of religion not only entertaining it but seeming to take it seriously. The locus classicus of this kind of thinking is the Vision of Ezekiel, which, most famously since Erich von Däniken (and, most creatively, Josef F. Blumrich!), has been claimed by some to be a premodern UFO sighting report, Ezekiel describing a(n) UAP and his interactions with the intelligence behind it according to the concepts and language at his disposal. Von Däniken sums up nicely the literalist reading of the opening of the Book of Ezekiel. He writes in Chariots of the Gods concerning Ezekiel’s likening “the din made by the wings and wheels to a ‘great rushing.’ Surely this suggest that this is an eyewitness report?” (39). There is much, however, that complicates matters. First, however much the Book of Ezekiel is the first written prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, its authorship is uncertain; the book attributed to “Ezekiel” is quite possibly the work of several hands. Then, the vision itself, for all its rococo detail is famously obscure in its complexity, as the many and varied attempts to concretely depict it attest, which suggests the description is perhaps more or other than a flabbergasted one of an alien object. Even if we take the vision to be an “eyewitness report,” the witness himself is not very reliable. As Michael Lieb writes in his invaluable Children of Ezekiel

Scholars marvel at Ezekiel’s experience of bodily paralysis and periods of trances (Ezek. 3:15, 4:4-6); his accounts of levitation (Ezek. 3:12-14, 8:3, 11:1); his cutting, weighing, dividing, burning, binding, and scattering his hair (Ezek. 5:1-4); his sudden clapping of the hands and stamping of the feet (Ezek. 6:11); and his belief in his power to destroy with speech (Ezek. 11:13). (14)

Jacques Vallée would likely point to Ezekiel’s paralysis, trances, and levitation as consistent with the kinds of paranormal after-effects often associated with close encounters. But Ezekiel’s other behaviours (above) are part of a more concerning pattern (if we insist on taking the book at face value):

He is told to shut himself within his house. He is bound with cords, and his tongue cleaves to the roof of his mouth so that he is dumb (Ezek. 3:24-26). He is given to prepare his food with dung (Ezek. 4:15) and to accuse his enemies of worshiping dung balls (the term dung ball is found more often in Ezekiel’s prophecy than anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible). (14-15)

Unsurprisingly, “[s]uch circumstances have prompted some scholars to see in Ezekiel evidence of an especially pronounced pathology.” Today, such an “eyewitness” would not be believed, even by believers in the Phenomenon.

However, such troubles are somewhat clarified when we understand how illegitimate it is to spontaneously take Ezekiel’s vision to be an “eyewitness” report by understanding that an “eyewitness report” is a modern genre of discourse and that of the book of Ezekiel another. As I have been at great pains here at the Skunkworks, it is an error to project an historically, culturally, and socially local communicative convention (here, the “eyewitness report”) onto temporally and culturally distant texts and artefacts. Simply, one need first situate the text in the context of the discursive practices of its day; even if it should, as something radically new, break with these conventions, that departure can only come into view in light of what the text leaves behind. Logically, Ezekiel’s vision is either exoteric (visible to Ezekiel and anyone else within visual range of the phenomenon), esoteric (visible only to Ezekiel, consistent with the vision’s being a variety of religious experience or an hallucination), or, perhaps, a powerfully original work of religious poetry with prophetic import and intent. That is, I propose, the “truth” of the Book of Ezekiel is not in its “facts” but in the consequences of its revelations for the spiritual life of its intended readership, which is to read the book rhetorically (which is unavoidable, even for the “literal”—whatever that might finally mean—reading). It is my contention that precisely such philologico-rhetorical reflection is demanded of all culturally and temporally distant “accounts of encounters with Non-Human Intelligences” and that such accounts cannot be admitted as warranted evidence until that due diligence has been undertaken. Why otherwise learned scholars tend to such literalism reflexively is another, however interesting, matter….

The revision of religion I term gnostic (or, perhaps, neognostic) is founded on the testimony of Experiencers coeval or historical. If we take our concept of gnosis from Hans Jonas’ The Gnostic Religion: the Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity (1958), gnosis is an immediate acquaintance with the divine (unlike that knowledge bestowed by faith or theological speculation). Not only is “[t]he ultimate ‘object’ of gnosis…God,” writes Jonas (35), but “its event in the soul transforms the knower himself [sic] by making him a partaker in the divine existence.” Gnosis, then, is a radically-transformative experience of the divine. Surely, the Experiencer (if we take their words prima facie) has experienced a Non-Human Intelligence and been changed by the encounter. In this sense, the tendency I explore here rests on a variety of gnosis. Insofar as this neognosticism rests on testimony distant in time and culture, that foundation is questionable; insofar as it appeals to contemporary, “Western” reports, its founding revelations are a variety of religious experience whose veracity is (to the say the least) contested, not merely on dismissively sceptical grounds. In either case, those who entertain this neognosticism, the conjecture that the history of religion is the history of encounters with Non-Human Intelligences, cannot claim to know this version of religion to be true, they can appeal only to the gnosis of those they designate as Experiencers.

If, however, we “bracket” the question of the (questionable) truth of the speculative revelation at the heart of this neognosticism, certain, curious implications come into view. In nuce, like the appearance of Flying Saucers within the horizon of the Cold War, neognosticism “stands in compensatory antithesis” (as Jung said of the Flying Saucers) not to the threat of atomic warfare (as after the Cold War) but the existential threat of global warming and ecological degradation. This neognosticism then appears reactionary, fleeing the chaos of the present and a threatening future into a premodern, paranoid (however “enchanted) “past;” positing a certainty (gnosis) in the face of anxious uncertainty; and taking flight from time (history) into an a-historicity, a timelessness if not an eternity.

The thesis that modernity is “disenchanted” does not go uncontested. What is less likely to be resisted is the relative material security of life in the so-called developed world. Vaccines and antibiotics defend us from viruses and bacteria that in the premodern world were unknown and often mortal, for example. Urbanization, agriculture, transportation, and communication domesticate the countryside at large, so that the experience of getting lost in a selva oscura differs dramatically from that in Dante’s day. Examples can be multiplied. This is not to say modernity is absolutely secure, the being of Dasein is Sorge, as Heidegger reminds us. But the objects or character of that worry differ markedly from that of premodernity. Relative to today, one might posit that the premodern, “demon-haunted,” enchanted world is paranoid, peopled by unseen, inscrutable agents responsible for all that out of human control (“Nature”). In such a world, one might see religion, its myths and practices, as a means to deal with an uncontrolled, uncontrollable, and, by extension, threatening nature. I do not mean to reduce religion to a kind of bartering (however much the etymology of ‘bless’ suggests at times it is), but rather to suggest one function of religion is to orient the human soul or society in the world-at-large. The present, post-Holocene moment, however, is devastatingly ironic, for it is precisely our harnessing that knowledge and know-how that exorcised those premodern threats that has unleashed a nature now even more menacing and uncontrollable than the one we so temporarily seemed to have tamed. The modern(ized) mind, however, does not fall back into the premodern paranoia (however much it succumbs to its own, “postmodern” versions in the face of occult forces, social and natural, malevolent or indifferent). The neognostic, however, does, believing in an unseen world peopled by Non-Human Intelligences of uncertain intent let alone morality. Jacques Vallée’s Control System Hypothesis is a case in point, as likely to be found in a novel by Thomas Pynchon or William Burroughs (where one does read of “Control”) as arising from the extensive files of a ufologist. Indeed, the neognostic seems all-too-Gnostic, as the classical versions expressed a belief in a malevolent cosmos controlled by daimonic Archons, a paranoid parody of the Babylonian astrological religions. In the face of the anxieties of a social world developed beyond comprehension, whose very natural roots are withering in the heat of the furnace of its own development, the neognostic fears not the real-world, social and natural threats but an Other world whose agents however inscrutable are at least palpable in their ephemeral, however sometimes terrifying, appearings.

Ours is surely an uncertain time, from the furor over “Postmodernism,” to post-truth, “fake news,” and deep fakes, to the disturbingly chaotic climate regime to unfold in the coming centuries, like none Homo Sapiens—indeed the earth—has experienced. In this situation, wherein nothing seems knowable, the Experiencer possesses gnosis, an apodictic certainty. The Experiencer’s gnosis, however, is radically other, in a way less, than their classical forebears’, for whom the experience of the identity of the soul with the essence of the Alien God was at the same time knowledge of “everything that belongs to the divine realm of beings, namely, the order and history of the upper worlds, and what is to issue from it, namely…salvation” (34). The Experiencer, rather, paradoxically is given access via the gnosis of the encounter to a mystery. What is their nature? What do they want? Are they benevolent, malevolent, or indifferent? Are they terrestrial, extraterrestrial, transtemporal, or interdimensional? This mystery, however, is grounded in a certainty, at the very least a self-assuredness, such as that on display at the most recent Rice University Archives of the Impossible conference, when an Experiencer shouted out, “We know there is another world!” Amid the present, real, threatening uncertainty, the gnosis of the Experiencer serves as a First Principle, an Archimedean point, or at least an anchor of real, unassailable knowledge borne of direct, first-person experience (the historical foundations of which certainty, again, are laid down in the inheritance of an historically, culturally local tradition…).

Just as the neognostic flees the disenchanted, out-of-control world for a premodern, enchanted-if-demon-haunted world and exchanges the deeply unnerving uncertainty of the present and foreseeable future for an unassailable if paradoxical certainty, they take refuge from history in an ahistorical simulacrum of eternity. At least since Kant and Heidegger (the first for whom time, with space, is the form of intuition and inner sense; the latter for whom Dasein is not only temporal but historical) the temporal situatedness of human understanding is a given, i.e., one whose concrete determinations are unfathomable, never to be exhaustively brought to the light of consciousness. The consequences of this temporal finitude play themselves out in our brief study of the Vision of Ezekiel. For the neognostic, temporality is assumed to be transcended in the unquestioned (unreflected) obviousness that, as the opening of the History Channel’s Ancient Aliens reminds us, “We have never been alone,” or, in the refrain of the neognostic, “The Phenomenon has always been with us.” On the one hand, perhaps, it is merely a common-sense, naive realism that underwrites this temporal blindness, a belief in human nature, as it were. More profoundly, this certitude in a “perennial philosophy” gestures toward that “other world,” which, if not exactly outside of space and time, lies outside (if however much aside) our own. This neognostic atemporality is, of course, from the point-of-view informed by philosophical hermeneutics (at least), a naive projection and imposition of the present horizon on those of the past, a kind of unconscious epistemic imperialism or colonialism, which blithely liquidates cultural difference in the assumed naturalness of its own universality. In the post-Holocene, unforeseeable but undeniable change aggravates a sense of temporariness to the point of imaginably foreclosing history itself in the misanthropic, schadenfreudlich fantasy of Near-Term Human Extinction. Little wonder the neognostic flees in fancy to some unchanging order amid a world civilization on the wane (just as the Gnostics themselves did).

As any reactionary tendency, neognosticism is unwittingly ideological, affirming the status quo at the hidden centre of society in spite of the marginality of its explicit beliefs. From a disenchanted, disillusioned present threatened by known, terrible forces the neognostic flees to an enchanted but paranoid world of occult agents. Over an abyssal uncertainty, they cling to a thread of gnosis, itself anchored, paradoxically, to mystery. In the face of an epochal shift, a timeless order is affirmed. But these understandable compensations twist around a root grounded in an affirmation of the very conditions that give rise to the disorder that motivates them, however unconsciously, and that is the very character of the Non-Human Intelligence it posits. As I have laid out repeatedly here at the Skunkworks, these “Non-Human Intelligences” are human-all-too human, whether with regards to their anthropomorphism or the fact of mutual recognition. What, further, remains unremarked and unexamined is the use of ‘intelligence’ to designate awareness, consciousness, or, more properly, soul. For what seems at work here is an Abrahamic/Gnostic assumption that centres human awareness as paradigmatic, essentially of the same order if not magnitude as that of God and those other created beings, celestial or infernal, between Man and God, Man being made, thus, in God’s own image. What is decentred here, pushed not only to the margins but out of sight, is the very real “nonhuman intelligence” of all the other nonhuman forms of life presently suffering a mass extinction, a Molochian sacrifice of biodiversity arguably underwritten by a certain strain of just this Abrahamic anthropocentrism that places the human being at the sole centre of creation as master over all other forms of life on earth. In this way, the neognosticism I sketch here colludes with the values that determine the social behaviour that results in the climate and ecological crises that determine its own advent. Ironically, it’s just the discourse that submits this neognosticism to critique of this kind that may rightfully call itself shamanic, if, by the shaman, we name the one who mediates between the human and truly nonhuman world.

An important ufological popularizer of the ETH is Donald Keyhoe. In his first book, The Flying Saucers are Real (1950), he wrestles with the question of the origin of the flying discs. Having been pushed to the ETH by a process of elimination, he tries “to imagine how they [ETIs] might look” (136). Having read what he could of what we today call exobiology, he understands that there are “all kinds of possibilities.” Then, he makes a telling confession:

An important ufological popularizer of the ETH is Donald Keyhoe. In his first book, The Flying Saucers are Real (1950), he wrestles with the question of the origin of the flying discs. Having been pushed to the ETH by a process of elimination, he tries “to imagine how they [ETIs] might look” (136). Having read what he could of what we today call exobiology, he understands that there are “all kinds of possibilities.” Then, he makes a telling confession: